The UK government has been financing the “impact” market infrastructure since 2011.

Social outcomes partnerships or social impact bonds (“SIBs”), known as “pay-for-success contracts” in the US, are emerging as a proposed financing instrument for healthcare globally. SIBs were implemented in the UK’s healthcare sector from 2014 and the UK now has the most health-related SIBs, with 15 out of 55 projects worldwide.

SIBs entrench societal-wide perverse incentives for conditions of inequality and scarcity.

Let’s not lose touch…Your Government and Big Tech are actively trying to censor the information reported by The Exposé to serve their own needs. Subscribe to our emails now to make sure you receive the latest uncensored news in your inbox…

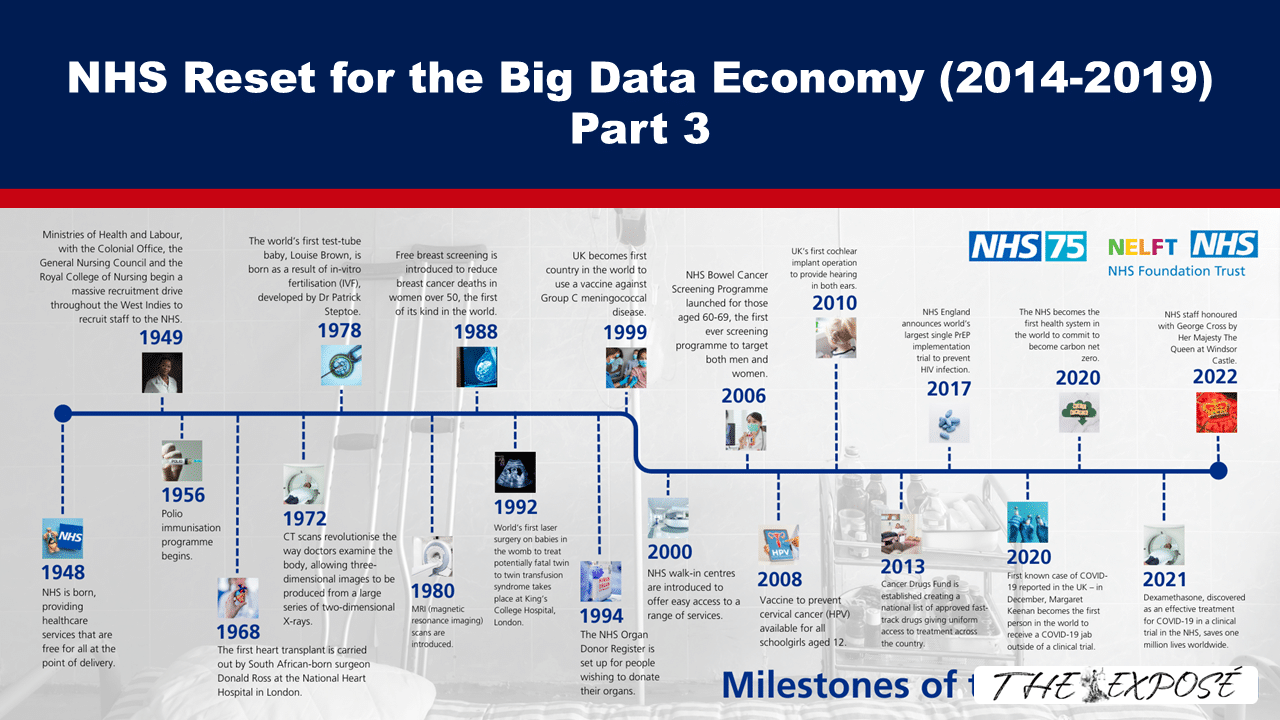

The Real Left is publishing a series of essays titled ‘The Health and Social Care Reset for the Big Data Economy’. You can read the first part, ‘The Great Health and Social Care Reset for the Big Data Economy Part 1.1’, which is a timeline of NHS capture during the years 1970s-2013, HERE.

The following is a section of the second part, which is a timeline of NHS capture during the years 2014-2019. We have published the essay in several parts because, totalling a little under 10,500 words, it’s longer than most would read in a single sitting.

The Great Health and Social Care Reset for the Big Data Economy Part 1.2

By Emily Garcia, as published by Real Left on 27 January 2026

Table of Contents

Social Impact Bonds and Impact Investing: A Brief Critical Explainer

The UK government has been financing the “impact” market infrastructure since 2011 through the Department of Work and Pensions’ (“DWP’s”) innovation fund, Big Society Capital, the Life Chances Fund, Commissioning Better Outcomes and, most recently, the Institute for Impact Investing’s funding of social impact bonds. [89]

Social impact bonds surfaced as a proposed sustainable financing instrument for healthcare globally in the Institute of Global Health Innovation report ‘Creating sustainable health and care systems in ageing societies’. [90] They began to be implemented in the UK’s healthcare sector from 2014, as explained below.

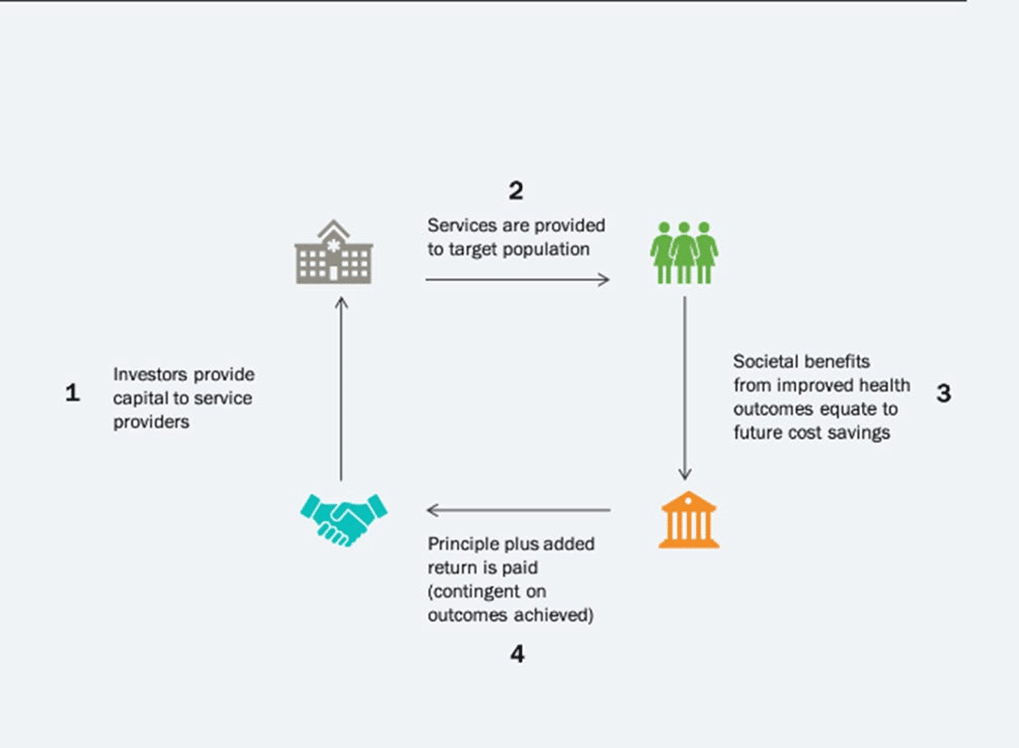

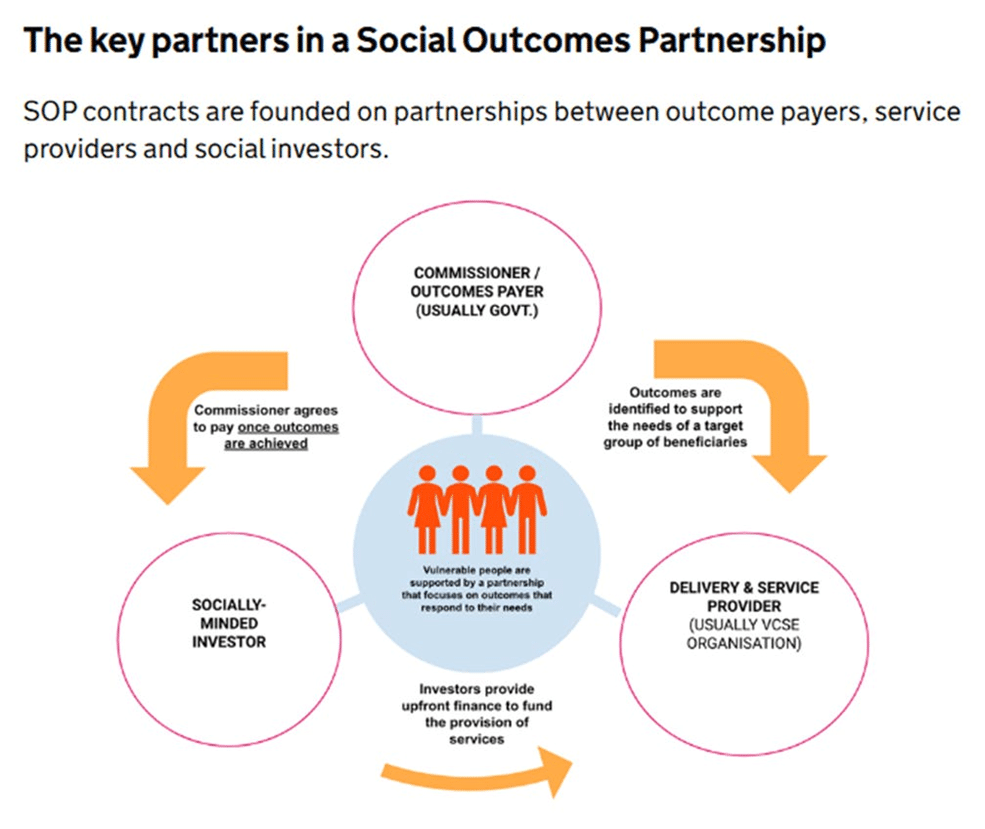

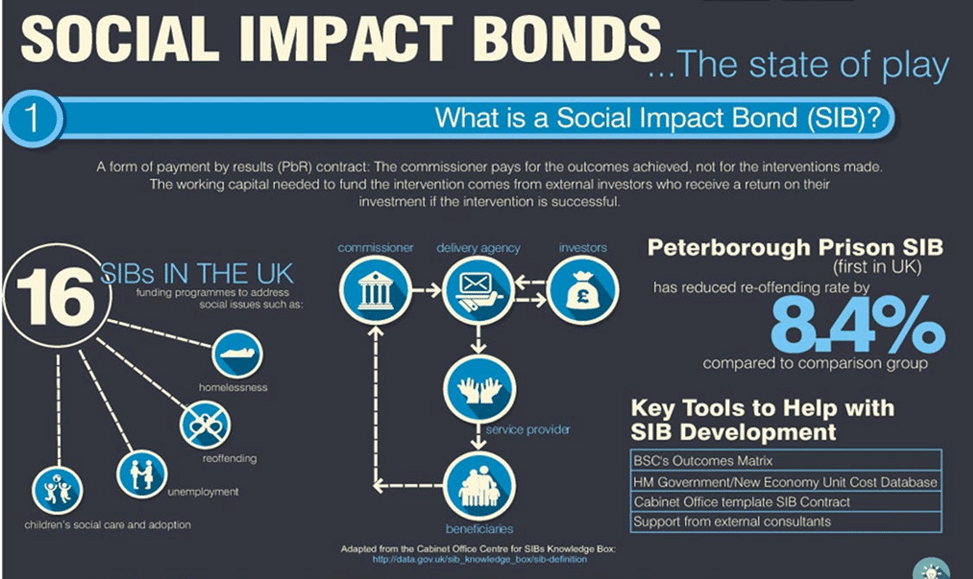

The Cabinet Office’s ‘Centre for Social Impact Bonds’ provides the following definition of social impact bonds (“SIBs”), also known in the UK as Social Outcomes Partnerships, and in the US as “pay-for-success contracts”: [91]

To qualify as a SIB … there must be:

- A separate contract between a commissioner and a delivery agency (sometimes called a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV));

- Payment from the commissioner for the achievement of one or more outcomes by the delivery agency;

- At least one investor legally separate from both the commissioner and the delivery agency; [and,]

- Some or all of the financial risk of non-delivery of outcomes sitting with the investor. [92]

The 2014 “Commissioning Better Outcomes” evaluation for the Big Lottery Fund: ‘Social Impact Bonds: The State of Play’, touches on potential problematic aspects of SIBs. Commissioners who were surveyed in the research that the report authors conducted identified the potential for metrics being set that create “perverse incentives.” [93] The report gives a theoretical example of such as payments for reducing the number of children in care, which incentivises the removal of children from care who, presumably for reasons of safety and well-being, should remain in the care system. [94] (See also reporting on the 2015 Goldman Sachs funded SIB in Utah that denied special education to over 99% of the students that were in the early childhood Pay for Success programme. [95])

An academic scoping review of SIBs for non-communicable diseases found, “Conflict of interest and lack of public disclosure were common issues in both the published and grey literature on SIBs.” [96]

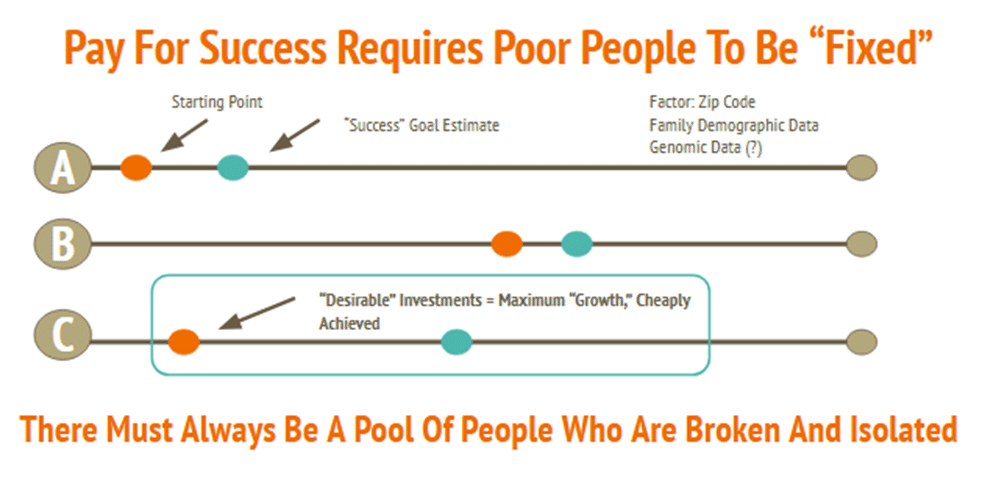

The Government Outcomes Lab concedes there has indeed been “evidence of gaming in SOPs, particularly in earlier contracts,” with providers engaging in “various forms of gaming,” including “creaming/cherry-picking” – such as selecting beneficiaries that are more likely to achieve the expected outcomes and leaving outside the cohort the most challenging cases, or “parking” – neglecting beneficiaries that are less likely to achieve the expected outcomes and leaving them outside the cohort. [97]

In the same way that Private Finance Initiatives cost the taxpayer more long-term (see Part 1.1), SIBs are ultimately a more costly way to finance the scaling up of preventive programmes than governments simply paying service providers to expand an intervention to more beneficiaries.

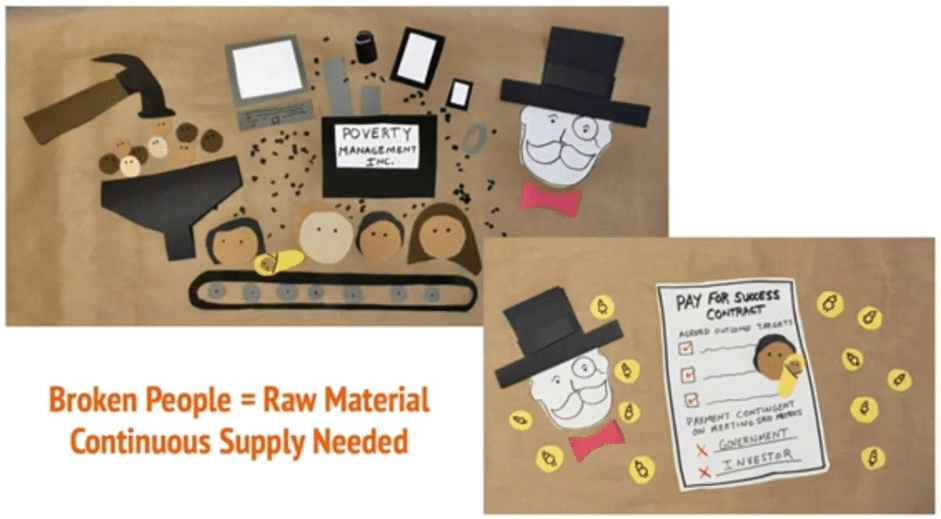

Some critics, with whom it is no doubt clear I agree, have gone further in their denunciations of social impact investing by arguing that it entrenches societal-wide perverse incentives for conditions of inequality and scarcity. [98]

Austerity is necessary both for the finance model (i.e. private investors’ involvement in “pay for success” contracts for the public services the government can “no longer afford”) and for growing the capitalisable markets in poverty-related social problems: homelessness, unemployment, poor mental and physical health, educational underachievement etc.

Research and Innovation’s report ‘The Future of Impact Investment in Healthy Ageing’ is explicit about the opportunities arising for “market players” from the “vulnerabilities linked to the expected economic fall-out” of lockdowns in the UK. [99]

The most lucrative profit opportunities from setting up these markets exist at the level of financialisaton by hedge funds in betting for and against outcome achievements, and trading on people as securitised debt products. [100]

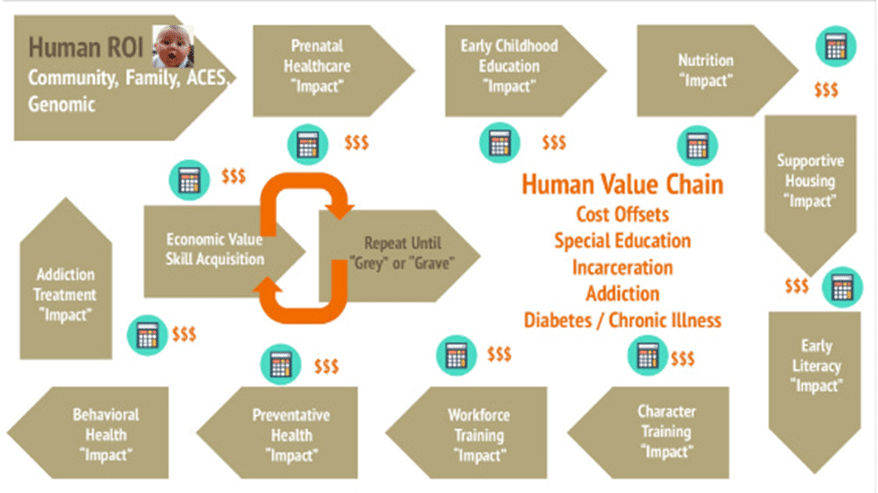

Within an impact economy, if successfully scaled, ordinary people will be expected to perform “self-improvement behaviours” to reduce their “debt burden” to society, with compliance incentivised through both carrot and stick behaviourist reinforcements, but primarily tied to the coercive lever of material dependency on this system for meeting their basic survival needs. This lever is likely to become ever more critical in the wake of the anticipated mass dispossession of workers, as a result of their human labour being displaced by Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies, principally AI and robotics. [101]

Another key reason for the push to implement social impact investing is the rationale it provides for embedding smart surveillance and real-time data gathering into service operations to track service users; essential infrastructure for an economy run on big data. This data can then also be used to train AI and robotics, the technologies earmarked to administrate the system.

Such changes are necessitated by the replacement of “contract frameworks, designed around activities and inputs” [102] by an outcomes measurement centred return-on-investment model. As Social Finance’s report on their Care and Wellbeing Impact Investment Fund (discussed in the following section) enthuses, amongst the ongoing positive impacts of its 14 “proof-of-concept” health and care sector SIB’s, “specific tools such as the dashboards are being adopted widely across the H&SC system,” and are being “extended to include additional data to look at things such as health inequities.” [103]

A fuller exploration of why the ruling class are attempting to orchestrate the transition to an impact-led economy, and how they have conspired to achieve this, is covered HERE, in Part 2 of this series, and in great breadth and depth on the blog and the YouTube channel [104] of Alison McDowell.

The Development of Healthcare Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) in the UK From 2014

Useful information on the history of the development of SIBs in the UK is provided in the aforementioned report, ‘Social Impact Bonds: The State of Play’:

Social Finance was launched in April 2008 to accelerate “the creation of a social investment market in the UK” (Social Finance, 2008). In August 2009 they published a paper (Social Finance 2009) arguing the case for Social Impact Bonds in a number of areas including reducing reoffending rates of short sentence offenders; reducing the number of young people entering Pupil Referral Units; reducing the need for residential placements for children in care; andreducing acute hospital spend through the increased provision of community-based care.[105]

Social Finance, co-founded by Sir Ronald Cohen (who is also co-director of the Global Impact Investing Network created in 2015 in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation, [106] and its predecessor the 2013 Social Impact Investing Taskforce [107]), set up the first ever social impact bond in 2010. This aimed to reduce short sentence re-offending rates of prisoners at Peterborough Prison.

16 SIBs in the areas of unemployment, homelessness and children’s social care and adoption were active in the UK by 2014, with multiple health and social care bonds under development. [108]

The Government Outcomes Lab (“GOL”) was set up by the UK government in partnership with the University of Oxford to investigate evidence around the use of social impact bonds. It shows that of the 55 pre-active (but contracted), active or completed health-related SIBs by 2025, 15 are in the UK, more than any other country. [109] The GOL Indigo dataset appears to be an incomplete listing, however, as several more projects are mentioned in a 2021 BMJ scoping review. [110]

Social Finance has played a pivotal role in promoting SIBs in health and social care through its “proof-of-concept” 2015 Care and Wellbeing Fund, designed to “stimulate the development and scaling of innovative community based models to manage long term conditions and care for older people,” and “to test different financing mechanisms such as social impact bonds (SIBs) and other forms of repayable finance/grants to fund activity and services in H&SC.” [111] Half the fund endowment was provided by Macmillan Cancer Support and the other half by Big Society Capital. [112]

The Fund devoted 50% of its assets to End of Life care outcome-based contracts (“EoLC”) for “innovative models that target preventative and community-based care,” because they found this health and social care sector offered better financial returns. [113]

In 2019, Macmillan launched the ‘End of Life Care Fund’ as the sole investor to continue work in End of Life (“EoL”) projects. [114] One of these was The Rapid Intervention for Palliative and End-of-Life Care (“RIPEL”) project, which reduced the number of days service users spent in hospital in the last year of life by 11 (on average), through launching home-hospice centred services. [115] It has been the biggest social outcomes contract in the NHS so far and the first one directly contracting with the service provider, Oxford University Hospitals. [116]

The fact that social impact investing was endorsed in NHSE’s Commissioning Guidance 2022 [117] and that the NHS Confederation’s chief executive Mathew Taylor called for every ICS to have “a portfolio of social investments” [107] the following year, has been held up by the Fund as evidence of its success in mainstreaming social Investment in the NHS.

The specific objectives sought in the EoL SIBs all revolved around reductions in “unplanned hospital activity,” or emergency admissions for those in care homes or identified as being “in their last year of life.” [118] Several projects, including Somerset’s ‘The Talk About Project’ [113] and Haringey’s ‘Advance Care Plan Facilitator in Care Homes’ [113] sought to achieve this through developing advance care plans with patients that, presumably, agreed to the withdrawal of life saving or life prolonging care, as Haringey saw a 14% reduction in emergency admissions following Advanced Care Plan implementation. [113]

The Highland Hospice EoL SIB feature in their ‘stories’ one “fiercely independent” cancer patient who “refused to be a burden to anyone,” [119] and another, a woman in her mid-60s, who decided to stop chemotherapy treatment for lung cancer. [120]

The introduction of SIB structures into the NHS that directly financially incentivise the withdrawal of medical care from patients considered to be “end-of-life” adds a concerning backdrop to the controversial Assisted Dying Bill, which could enable such cost savings through early physician-assisted suicide. 80 safeguarding amendments from critical Members of Parliament have been rejected in the House of Commons [121] (the Bill is now being debated in the House of Lords).

References

- [89] Department for Culture, Media and Sport. Social Impact Bonds: An overview. 2017. [Online video]:

- [90] Hope, P., Bamford SM., Beales, S., Brett, K., Kneale, D. et al. Creating sustainable health and care systems in ageing societies: report of the ageing societies working group. London: Imperial College; 2012 [Online]: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/institute-of-global-health-innovation/public/Ageing.pdf

- [91] Cabinet Office, Department for Culture, Media and Sport and Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Social outcomes partnerships and the Life Chances Fund. 16 November 2012. [Online]: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/social-outcomes-partnerships (https://archive.is/ouJte)

- [92] Fox, T., Hickman, E., Ronicle, J., Stanworth, N. Social impact bonds: the state of play. November 2014. [Online]: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resource-library/social-impact-bonds-state-play/ p. 1

- [93] Fox, T., Hickman, E., Ronicle, J., Stanworth, N. Social impact bonds: the state of play. November 2014. [Online]: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resource-library/social-impact-bonds-state-play/ p. vi

- [94] Ibid., p. 27

- [95] Ravitch, D. ‘Warning! ESSA Threatens Special Education.’ 2 December 2015. [Online]: https://dianeravitch.net/2015/12/02/warning-essa-threatens-special-education/ (https://archive.is/5kNpf)

- [96] Hulse ESG., Atun, R., McPake, B., Lee JT. ‘Use of social impact bonds in financing health systems responses to non-communicable diseases: scoping review.’ BMJ Global Health; March 2021 [Online]: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7938989/ (https://archive.is/qrVJm)

- [97] Ibid., p. 96

- [98] Cudenec, P. ‘Wising Up to the Impact Scam.’ Winter Oak Publishing; May 2023. [Online]: https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/impact.pdf (https://archive.is/WrAZy)

- [99] Crampin, H., Woods, T. The future of impact investment in healthy ageing: Report of key findings and recommendations from a study commissioned by UKRI. UKRI and Collider Health; November 2020. [Online]: https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/UKRI-131120-SocialInvestmentReport-V2.pdf p. 8

- [100] Real Talk With ZSJ. Episode 10: What’s the connection between hedge funds & educational and social justice causes? Youtube;28 January 2021. [Online video]:

- [101] Monaghan, C., Joury, S., Laláková, E., Woerdeman, S. Fertile Ground: A mapping and analysis of the vibrant ecosystem of organisations across Europe working to transform our economic system. Commissioned by Partners for a New Economy. October 2025. [Online]: https://www.metabolic.nl/publications/fertile-ground/ p. 19.

- [102] Kawa, L. The care and wellbeing fund: a retrospective. Social Finance. September 2022. [Online]: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/assets/documents/care_and_wellbeing_fund.pdf p. 33

- [103] Ibid., p. 34

- [104] Alison McDowell. On Impact Investing, Digital Identity and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals. Youtube; 11 March 2020.

- [105] Fox, T., Hickman, E., Ronicle, J., Stanworth, N. Social impact bonds: the state of play. November 2014. [Online]: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resource-library/social-impact-bonds-state-play/ p. 11

- [106] The Rockefeller Foundation. ‘Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN).’ [Online]: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/bellagio-bulletin/from-the-archives/global-impact-investing-network-giin/ (https://archive.is/DshRP)

- [107] Gov.uk. ‘Social Impact Investment Taskforce.’ [Online]: https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/social-impact-investment-taskforce (https://archive.is/lgkF5)

- [108] Fox, T., Hickman, E., Ronicle, J., Stanworth, N. Social impact bonds: the state of play. November 2014. [Online]: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/resource-library/social-impact-bonds-state-play/ p. 14

- [109] Government Outcomes Lab. ‘Impact Bond Dataset: Policy Sector: Health.’ [Online]: https://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/knowledge-bank/indigo/impact-bond-dataset-v2/?query=&policy_sector=Health (https://archive.is/BS7zR)

- [110] Hulse, ESG., Atun, R., McPake, B., Lee, JT. ‘Use of Social Impact Bonds in Financing Health Systems Responses to Non-Communicable Diseases: Scoping Review.’ BMJ Global Health. March 2021. [Online]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7938989/

- [111] Social Finance. The care and wellbeing fund: a retrospective. London: Social Finance. September 2022. [Online]: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/assets/documents/care_and_wellbeing_fund.pdf p. 7

- [112] Ibid., p. 3

- [113] Ibid., p. 10

- [114] Saunders, K. ‘Team Work Refines Social Finance Model.’ Healthcare Financial Management Association. 25 April 2025. [Online]: https://www.hfma.org.uk/articles/team-work-refines-social-finance-model (https://archive.is/Wlsg0)

- [115] Social Finance. ‘Pioneering Social Investment: the Macmillan End-of-Life Care Fund.’ 30 June 2025. [Online]: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/insights/helping-people-to-live-and-die-well-the-team-behind-ripel-an-innovative-palliative-and-end-of-life-care-service-in-oxford (https://archive.is/N6SvZ)

- [116] Social Finance. ‘Improving End of Life Care Through Co-Designing and Scaling New Approaches.’ [Online]: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/work/improving-end-of-life-care-through-innovative-finance (https://archive.is/ccgej)

- [117] Social Finance. The Macmillan end of life care fund. September 2023. [Online]: https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/assets/documents/Macmillan-EOLC-Fund-Overview-Sept-23.pdf p.2 (https://archive.is/Eu9cP)

- [118] Social Finance. ‘End-of-Life Care Projects Enabled Through the Care and Wellbeing Fund and the Macmillan End-of-Life Care Fund.’ [Online]:https://www.socialfinance.org.uk/our-end-of-life-care-projects (https://archive.is/FlNtH)

- [119] Highland Hospice. Case Studies: Liz’s story. [Online]: https://highlandhospice.org/uploads/library/EOLCT-Case-Study-Lizs-story-June-2024.pdf (https://archive.is/R0dpE)

- [120] Highland Hospice. Case Studies: Shirley Ann’s story. [Online]: https://highlandhospice.org/uploads/assets/EOLCT-Case-Study-Shirley-Anns-Story.pdf (https://archive.is/blOhK)

- [121] Right to Life News. ‘Week Three Wrap-Up: Over 80 Amendments to Better Protect the Vulnerable from Assisted Suicide Rejected.’3 March 2025. [Online]: https://righttolife.org.uk/news/week-three-wrap-up-over-80-amendments-to-better-protect-the-vulnerable-from-assisted-suicide-rejected (https://archive.is/jL2iu)

Featured image taken from ‘NHS75 – History of the NHS’, NHS North East London, 4 July 2023

The Expose Urgently Needs Your Help…

Can you please help to keep the lights on with The Expose’s honest, reliable, powerful and truthful journalism?

Your Government & Big Tech organisations

try to silence & shut down The Expose.

So we need your help to ensure

we can continue to bring you the

facts the mainstream refuses to.

The government does not fund us

to publish lies and propaganda on their

behalf like the Mainstream Media.

Instead, we rely solely on your support. So

please support us in our efforts to bring

you honest, reliable, investigative journalism

today. It’s secure, quick and easy.

Please choose your preferred method below to show your support.

Categories: Breaking News, UK News